A Brief History of Popular Music: The Jazz Age

The American tradition that leads to Elvis, Michael Jackson, and Taylor Swift starts with the descendants of slaves in the South and migrants in the North.

The two candidates I have singled out for the first “pop song would be Scott Joplin’s “Maple Leaf Rag” and “After the Ball.” Written by Charles K. Harris. Harris’ number is far less remembered than “Maple Leaf Rag”, but “After the Ball” came earlier, becoming the first song in American history to sell over a million copies. The song itself isn’t particularly remarkable, it is a fine number about a man recalling a woman breaking his heart, how after the ball his hopes were gone and he could never love again. What is far more interesting is the mechanisms by which the song came to be. New York City’s Tin Pan Alley referred to a street littered with music publishing houses, where dozens wrote the songs that would define the Great American songbook. George Gershwin, Irving Berlin, Harold Arlen, Dorothy Fields, Fatz Waller, and Scott Joplin all started there or worked there, and every one of them was a major force in the music that was played over the first radios. Tin Pan Alley is not only influential for defining the style of music in that era, but also for being a place where music was mass produced. Popular music wasn’t the domain of traveling singers whose numbers would travel with them and any who heard it, popular music was sheet music being bought and sold near you. It was something factory-made.

“Maple Leaf Rag” represents another end of popular music’s spectrum. A Rag as a style of dance or music had been around in Black American communities for decades, but the style of ragtime first reached a national audience when the style was performed at the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair. Though Joplin was only a modest success in his lifetime, his work lives on as piano classics. I bring up his music not only because of his importance as one of America’s first great musicians and a pioneer in one of America’s first distinct musical styles, but because of ragtime as a phenomenon. Over a short period of time, a new, energetic style of music came around from young Black artists. This is an essential trend in popular music that constantly repeats itself. The moment a style gets old, a new crop of artists comes around and flips culture on its head.

The other important factor in these songs is in their creators. Harris, like many of Tin Pan Alley’s songwriters, was Jewish. Joplin was the son of a freed slave. The history of popular music (like most if not all of American history) is directly tied to oppression. Here lies a core paradox of popular music. It is often a way for marginalized people to express themselves, but it is often for or even by the very people who marginalize them. Much of ragtime’s popularity was through minstrel shows, where performers (both Black and white) would darken their faces and perform highly stereotyped songs or scenes. It is a fair question to ask if pop music is a proper way to represent culture or if it cheapens it. The original ragtime of the nineteenth century was improvisational, played by people who usually couldn’t read sheet music. Does teaching ragtime as a rigid, written thing (as “Maple Leaf Rag” is often taught to piano students) weaken it as an art form? Did ragtime’s ascension to popularity make it less of a Black art form? A simple yes or no to either question feels wrong.

On some level, pop music must be shallow. If there is too high a barrier for entry then a piece will struggle to reach a mass audience. Yet that mass audience might just carry that song in their hearts until they stop beating. In pop music we can find something greater than any individual person, place, or time, yet defined by all three. Few things can rally a group of radically different people like the right song. That ability to reach people and connect with them, even if only through a catchy melody, is something valuable. It may not have all the cultural depth of traditional folk or the experimental nature of scholarly art music, but it has its own value.

SO: The history lesson aside, how should you get into pop music?

This series aims to provide a broad guide to trends, building them into a continuous historical narrative. All the world is a stage, and the passing of time is a play’s acts beginning and ending. As such, I’ve divided this series’ subjects into “acts” that all have their own “scenes”. These distinctions are not made from anything more than my whims, or how I feel songs go together. These acts are not divided into exact chronological periods because culture cannot be divided into exact chronological periods. There is often no clean dividing line in a work’s genre or place in culture, so even if a song is from the 60s I might fit it next to a song from the 30s or 40s. Without further ado, let's look at American popular music’s first act.

Act 1: The Jazz/ Pre-Rock’n’Roll Era

This period ranges from the earliest big recordings to the early 60s. Given that many of these songs are almost 100 years old, very few songs from this era have a direct connection to the modern day, but they’re still powerful, worthwhile and a vital through-line to modern music.

Scene 1: Tin Pan Alley/Vocal Jazz.

Jazz was the defining trend of this era, and while this era’s instrumental jazz is a touch beyond my knowledge, I do feel equipped to speak on vocal jazz. This era often saw many singers doing their takes on the same number, the artists themselves lacking much of a signature beyond their vocals. This is not at all to diminish the singers themselves, as their work stands as some of the best vocal performances in history. You could scan through collections of Ella Fitzgerald, Billie Holiday, Nat King Cole, or Ray Charles and with each one discover masterpieces.

To pick a few specific numbers, it is worth remembering the history of this era and its past. Jazz, like ragtime before it, was a hip new art form pushed by young Black artists. It dealt with the same issues ragtime did. Though unlike ragtime, jazz remained a strongly Black art form due to a backlash against it alongside pushes from the genre’s proponents.

This era intersects heavily with Musical Theater, and as such my first big recommendation is from a work that can be argued as the first musical, Show Boat. The work leans into themes around single motherhood and miscegenation. The show was not perfectly woke (it was first performed in 1927, of course it wasn’t), featuring blackface as many Broadway shows did, but it also featured one of Broadway’s first integrated casts. The novel the show was based on used spirituals to frame the book’s narrative on the Mississippi River, and Jerome Kern and Oscar Hammerstein II, the composer and lyricist of the show, expanded on that with “Ol’ Man River.”

Most famously performed by Paul Robeson, the song compares the overbearing oppression of Black Americans with the eternal flow of the Mississippi River. Robeson would often change the lyrics as he performed the song outside of the show, replacing the n-word and changing the song’s ending. This was done to reflect the growing movement for civil rights. Within the show, his character, Joe, was resigned to his fate, the song a lament about his situation’s injustice. Robeson changes the lyrics, turning the song’s message to one about fighting impossible odds, the flowing river no longer a force that carries the downtrodden with it, but a grand universal force that with a bit of work, will push society towards justice.

In a similar vein I’d recommend Ray Charles’ “Georgia On My Mind.” Charles is a legend whose influence and power cannot be understated. A part of me even regrets picking “Georgia” over “Hallelujah, I Love Her So” or the incredible “What’d I Say Part I and II,” but “Georgia on My Mind” is special. The song was written by Hoagy Carmichael and Stuart Gorrell, Tin Pan Alley songwriters, but Ray Charles is the one who elevated it to its legendary status.

People often claim the song was written about Hoagy Carmichael’s sister, but regardless of whether the written intent sees Georgia as a woman, Ray Charles is singing about the state. Georgia was his home state, and by Charles’ version’s release it was a major battleground for the civil rights movement. Georgia was the homeland of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and a center of Black culture. In the powerful voice of Ray Charles, Georgia’s calls to him are more than homesickness or a yearning for a loved one, it’s a connection to his roots and his culture.

CW: this next song is about lynching. It’s the heaviest song I’ll put on this list, and maybe the heaviest song in the American canon. If you’d like to skip it, just skip this upcoming paragraph.

My closest comparison to Strange Fruit is the body of Emmet Till. Much like the horrific photo of the boy’s lynched body that rallied Americans against racism, “Strange Fruit” places the unspeakable front and center in a way you can’t ignore. In Abel Meeropol’s lyrics, the beauty of the land is contrasted by the terrible violence within it. The trees have been so heavily watered by the blood of Black bodies that blood is on the roots and the leaves. These powerful words are elevated incredibly in their most famous renditions by Billie Holiday and Nina Simone. Both versions are harrowing and incredible. What a terrible, terrible thing that this song is still relevant today with the lynching of Demartravion “Tray” Reed, whose body was found hanging from a tree on Delta State University in September 2025, and was ruled a suicide.

On a very different note, this era includes an interesting post-WWII cultural shift towards Latin America. With places like Paris and London recovering, American audiences shifted their attention to their Southern neighbors, and their musical styles of Salsa, Calypso, Mambo, and Bossa Nova among others. Of this boom, the most notable artist is the legendary singer, actor, and activist Harry Belafonte (Day-o/The Banana Boat Song, Jump In the Line, etc.), but the most notable song is “The Girl from Ipanema.”

Unlike the previous songs, this one is a simple love song about a man watching a girl go by and wondering why he’s so lonely. On its surface, it’s an unremarkable good song, one of many collaborations between American jazz artists and Latin American counterparts. The difference is that Stan Getz and Joao Gilberto’s iconic number is one of the most recorded songs in the world, only behind The Beatles’ “Yesterday.” That’s the power of popular music. An innocuous song that’s often mocked as elevator music is also one of the most recorded, most beloved songs in history.

Scene 2: Frank Sinatra

The 50’s was a time of icons, and few rivaled Ol’ Blue Eyes. Sinatra’s lengthy career could fuel many articles on its own, but I’ll limit myself to a few of his most important songs. There are plenty of iconic tracks, “My Way,” (which actually came long after this era) “New York New York,” “Blue Moon,” and one I reccomend strongly - “I’ve Got You Under My Skin.”

“I’ve Got You Under My Skin” is a stone cold classic love song from legendary singer and songwriter Cole Porter. Comparing Ol’ Blue Eyes' version to earlier versions from Virginia Bruce or Roy Noble and his orchestra, Sinatra is much more loose. Swing as a concept is rather simple musically, but Sinatra shows it’s a lot more than just playing with time in a song. He sounds relaxed. It isn’t just that this love has become a deep part of him, it’s mundane. There’s no reason to get melodramatic during the verses, he’s stating a simple fact. This looseness lets him play with the meter, delivering lines in a perfectly charming way. The real grab is the arrangement from Nelson Riddle. That opening horn line is iconic, and the solo is a perfect escalation. With the best songs there’s a push and pull, and this solo is a big push that allows Sinatra to pull it back with the final chorus, and slowly push that to a climax that drops out in a perfect, quaint way to fit the song’s quaint love.

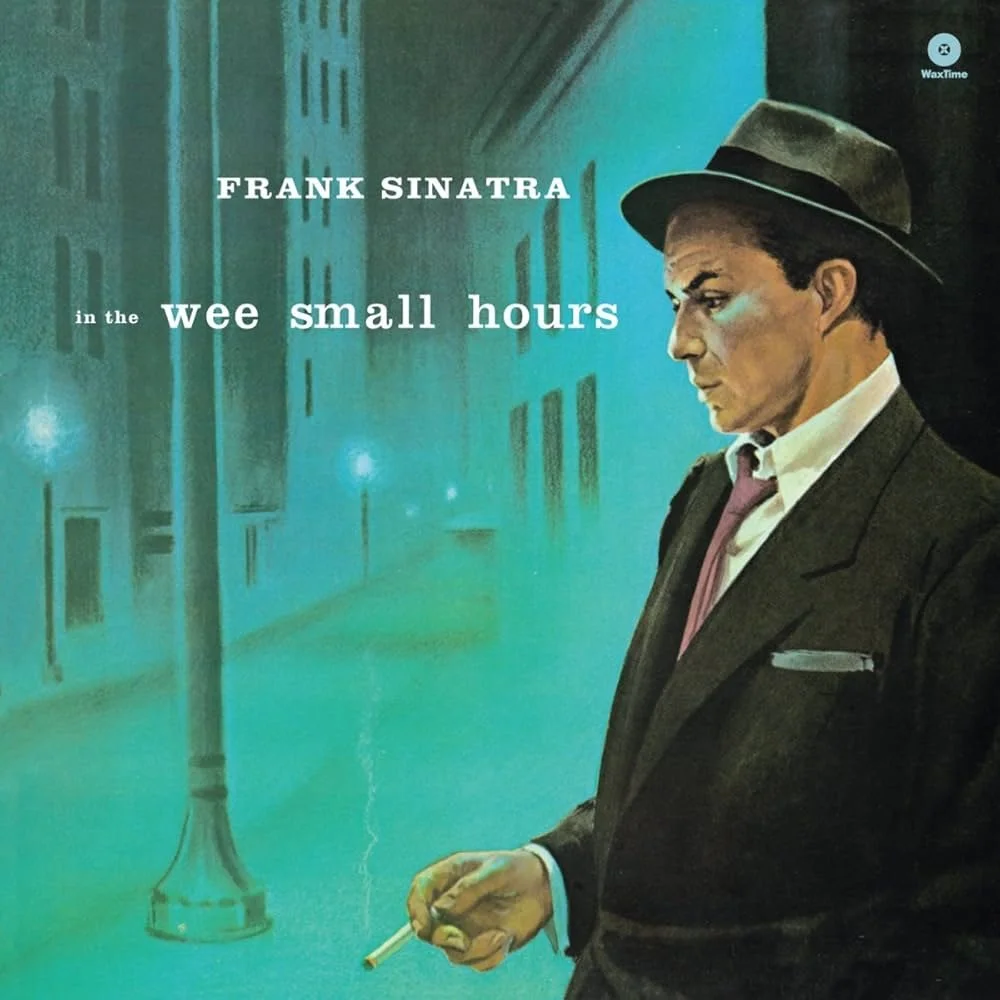

Sinatra’s masterpiece, however, is the 1955 album In the Wee Small Hours. The album’s importance to consumers begins with the cover.

A link to a playlist of the whole album is here

Before this album, most cover art was a photo of the artist with eye-catching typography listing the title. “Small Hours”’ cover resembles Edward Hopper’s legendary “Nighthawks”, with its themes of isolation and loneliness. Sinatra is in a similar place, stewing in the noir aesthetic’s defining isolation. Where gangster movies use that isolation to comment on violence, there’s none of that here. The isolation is something that pushes inwards towards the painting’s depiction of Sinatra. The building behind him melds into the sky, the road melds into the sidewalk, the sidewalk melds into the buildings, the only fully defined figure being Sinatra. It is a powerful expression of the inward-facing music within the album.

Another factor is the format. Like most popular music, it was released as two ten-inch records, but Sinatra wanted the album to be formatted in the same manner classical music was; one 12-inch LP. This would soon after become the format for all albums to come, one of many ways this album was ahead of the curve. It’s also worth examining the word “album”, as “In the Wee Small Hours” can be considered the first album. Before it, most “albums” were albums in the sense of a photo album- a collection of songs as a photo album is a collection of photos. There wasn’t a great deal of thought as to how the songs combined to form one unified work, albums were a way for fans to have a mix of singles and deep cuts (usually covers).

“Wee Small Hours” is, besides the title track, all covers, but Sinatra redefines them to make one cohesive work. The album draws heavily from his real life, where his relationship with his second wife Ava Gardner was failing terribly. Though the two would only divorce in 1957, their relationship was messy for years. Their relationship began as an affair during Sinatra’s first marriage, and through his second both would have numerous affairs that triggered mutual jealousy. All that heartache came out on record, including on the devastating “When Your Lover Has Gone”, where Sinatra broke down in tears after singing the master recording. Nelson Riddle arranged this album, and his work is to Sinatra’s performance what a score is to a film. Not only in the literal sense of it being backing, but in the way it enhances all the emotion of a moment. The gentle strings that reveal the ironic delicateness of “I Get Along Without You Very Well” are a particular highlight, alongside the puddle-stomping muted trumpet of “Mood Indigo”. “In the Wee Small Hours” is popular music’s first defining album, and to this day you could say it’s the greatest album ever made.

Scene 3: The Blues

In the late 1920’s there was a boy called Robert Johnson who wanted to play the blues. People who knew him claimed he wasn’t very good at it. But one year he left town, and when he came back he could play like nobody else. The legend is that on that trip away Robert Johnson sold his soul to the devil so he could play the guitar like no other man could. Johnson would die at the age of 27 in 1938, the first of many incredible young musicians to die at that age. The many gaps in the historical record only add onto the legend, as to this day we don’t know how Johnson died. Could it be that the devil had come to collect Johnson’s soul debt?

We’ll never truly know, but it’s a legend Johnson leaned into with songs like “Cross Road Blues,” “Me and the Devil Blues,” and “Hellhound on my Trail.” If you listen to the collection of his work, King of the Delta Blues Singers you’ll hear the source of Rock and Roll music.

The Blues is a lot more than a style of music that evolved from slave songs as freedmen and their children traveled across the Mississippi river, it’s the language of Black America. If you know how to hear it you’ll hear the blues in funk, soul, hip-hop, and in the ways people talk to each other every day. The legendary Black American playwright August Wilson described it incredibly through the words of his character Gertrude “Ma” Rainey in his play Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom, “White folks don’t understand about the blues… They hear it come out, but they don’t know how it got there. They don’t understand it’s life’s way of talking. You don’t sing to feel better. You sing ’cause that’s a way of understanding life. . . . The blues help you get out of bed in the morning. You get up knowing you ain’t alone. There’s something else in the world. Something’s been added by that song. This be an empty world without the blues. I take that emptiness and I try to fill it up with something.”

All the music I’ve talked about thus far is the blues. You could argue that nearly all American music is the blues. It’s important to understand that Ma Rainey isn’t saying that White folks can’t understand the blues, just that (for the most part) they don’t. The play takes place in 1927, in the era of Jim Crow. Some White people might understand the blues, but the people buying jazz records, most people you’d meet on the street, and the people who accepted that immoral order did not. This digression on race is not to distract from the history at hand, but to frame the many, many discussions about race and authenticity in music.

If you’re into guitar music I cannot recommend the works of blues legends like BB King, Lead Belly, and Muddy Waters enough, but while they are absolutely influences on the rock music to come, the progenitor I’d like to highlight is Sister Rosetta Tharpe. You can see Tharpe’s influence just from a photo.

Her bright smile and dynamic pose with her guitar are a clear landmark for every early rock n’ roller. And though most videos you’ll find of her are from the 1960s, it’s clear her performance style was equally influential (See: “Didn’t it Rain,” “This Train,” and “Up Above My Head” . She’s not a song-and-dance performer, and she’s much more than a pretty voice. She oozes power. Part of that control over an audience comes from her history with the church. Much like a good preacher, her passion could grab you from a mile away.

That power is referred to in performance studies as the divine. It’s Freddy Mercury at Live Aid. It’s Michael Jackson making crowds lose their minds with the slightest twitch from stillness. It’s Prince singing Purple Rain at the Superbowl. It’s Kendrick Lamar performing Not Like Us five times at the Pop Out and the crowd singing it a sixth time after the show. People online joke about aura, but the jokes work because the concept is real. Some people can achieve mastery over audiences that defies reason. If you try and understand that, you’ll understand how the blues fills up the empty world.

Though I see that divine power in Sister Rosetta Tharpe, the doors weren’t open for a woman like her. This is an era of segregation. Women had only been allowed to vote since Tharpe was five years old. But the other force pushing against Tharpe was her religious beliefs. Like many Black artists before and after her, Tharpe was religious and mixed that background with secular music. There would eventually be fertile ground in this intersection, but in Tharpe’s day it marred her in controversy. The backlash to “Rock Me” is particularly important as an early example of the ways society polices sexuality; especially Black sexuality, Women’s sexuality, and Black Women’s sexuality.

One of many important distinctions about this era’s popular music is that most songs were not written by their singers. Most of Tharpe’s songs are spirituals or blues standards, and the same is true for Sinatra and most vocal jazz singers (the standards being from Tin Pan Alley rather than the church). In my youth, this was a mark of serious inauthenticity, after all, the guys in Backstreet Boys didn’t even play their own instruments! What do you mean these people don’t write their own songs?!

Statements like that ignore the artistry behind their performances, but they come from an anti-pop ethos that, paradoxically, is an important part of popular music’s history. You can tie this sentiment to a billion different ideas and origins including the competitive nature of jazz and the competition capitalism forces upon all artists, but here I will choose to tie it to a concept of “reality” best exemplified in this era by Woody Guthrie.

A true American legend.

Guthrie was a man of the land. He sang songs about his own experiences and beliefs that he personally wrote. His album Dust Bowl Ballads (another masterwork I’d talk more on if I hadn’t already written an article on it) was drawn from his own experiences fleeing the midwest during the dust bowl period. He originated the now legendary label “this machine kills fascists” by smacking it right on his guitar. In response to Irving Berlin’s “God Bless America,” he wrote “This Land Is Your Land.” Where Berlin made his patriotism a grand, god-blessed thing that could be sung with a grand chorus and orchestra, Guthrie’s song is simple as simple can be. And while “This Land Is Your Land” is a patriotic song, it does not ignore the problems of America. Guthrie saying this land is ours is not a manifest destiny-evoking statement of American righteousness, but a call for political action. I read him contrasting the sky and valley above and below the highway as an environmentalist message- this land is made for you and me so we must preserve it. In a verse that’s often cut he sings against private land ownership, saying that this land is ours in a near explicitly communist manner- this land is made for you and me so we must seize ownership of it away from the bourgeois dictatorship.

Guthrie’s image as a white, low-class, common-man-championing country singer is often hijacked by conservatism, but his leftism is a key part of his persona and his place in history. People make hay over who is a real leftist or not all the time, and when people ask if someone is real or fake in music it’s a similar question. It’s easy to talk the talk, but if you haven’t or don’t walk the walk people are gonna be upset. If you want to be someone people like for an extended period of time, you can’t just be a pretty face with a pretty voice, you need to be something unique. The easiest way to do that is to be yourself.

The great irony in that idea is that the self, especially a version of yourself you put in your art, is constructed. Guthrie is, in popular culture’s mythology, the definition of authenticity and truth, but much of his teachings on the artists commonly considered his disciples came secondhand from Ramblin’ Jack Elliott. Elliott studied under Guthrie, and taught his style to Arlo Guthrie and Bob Dylan (who we’ll hear a lot more from later), but who could say was lost in that short game of telephone. Even if nothing was, Elliott told Esquire magazine that, “Woody didn’t teach me. He just said, ‘If you want to learn something, just steal it - that’s the way I learned from Lead Belly.’”

In the next act in the stage play of popular music’s history, we’ll see the result of one man whose “stealing” would change American culture forever.