The Best Songs: Bruce Springsteen and the American Dream

Nothing can fully represent America. The nation is too big, too populous, and too diverse for that to be possible. You might paint a lot of trees, but no one painting can properly show a forest. Bruce Springsteen is the closest anyone has ever come to truly showing the great forest that is the United States of America. From Bob Dylan and Woody Guthrie he took a persona of a humble truth-telling folk/blues man. From Black America he took a wild vocal style, soulful demeanor, and a near-religious power. From California and New York he took the soaring ambition that can only fully manifest when you’ve seen the bottom and the top of the world. From the South he took a fast tempo and raw grit. Most importantly, he took his stories from the American people.

Springsteen’s breakthrough album Born to Run begins with one of these stories. “Thunder Road” opens like a film. We get a lyrical establishing shot of Mary, who dances on her porch as the radio plays Roy Orbison. We’re instantly charmed by the narrator who teases “you ain’t a beauty, but hey, you’re alright/ oh, and that’s alright with me”. But even at this simple beginning the focus is on the road ahead of them, and The Boss’s narrator tells Mary as much when he asks her to, “show a little faith, there’s magic in the night”. Springsteen never elaborates on what this Thunder Road truly is; he doesn't need to. Thunder Road is just the goal. It’s wherever Mary and him can find their love and freedom unbound from any element of their past. As Springsteen belts before the band blasts away the song’s last minute, “it’s a town full of losers, I’m pulling out of here to win!”

Born to Run is an album overflowing with words. Something in Springsteen’s beer-drunk mumble makes the songs feel more organic than his peers. He bypasses every artifice and places you right in the middle of the most powerful emotions one can feel. Most of the albums that focus on such intense emotions are dour (I think of the tumult on Fleetwood Mac’s Rumors or the wails of frustration on Nirvana’s In Utero), but Springsteen is a rare artist who can bring positivity with the same overwhelming power that’s often reserved for angry or sad music. But it’s a vast oversimplification to call the album happy.

Take “Night”, the album’s third song. The song soars like every song on the album, but the lyrics paint a dark portrait fitting the song’s title. Springsteen sings about someone who works a nine to five and only finds the freedom that defines the album in the night. When I said that Springsteen showed all of America, I meant it. While Born to Run is as positive as many of The Boss’s albums, the joy found in the album’s narratives is always in a powerful contrast with a down-pressing society. Springsteen hit it big after the hippie movement’s collapse, but he has a hippie’s hope. In 1975, The Boss was witnessing a society in chaos. LBJ started a war on poverty and poverty won. Richard Nixon and his successors waged war on drugs; by which he really meant the anti-war movement and poor Black American communities. The Vietnam War had ended in complete disaster, with millions of Americans either dead or traumatized for no real purpose. There were a lot of reasons to be hopeless, but Born to Run lives as a strong counterexample.

Every song on the album is about love, but “Tenth Avenue Freeze-Out” has the honor of being about both love and music. The lyrics are the least direct on the album, but they tell the story of the E-Street band forming. On the song, The Boss struts his stuff with a James Brown swagger, hollering that it, “Seem like the whole world walkin’ pretty and you can’t find the room to move/ Well, everybody better move over that’s all/ ‘Cause I’m running on the bad side and I got my back to the wall!” Springsteen himself can’t find the words for what a Tenth Avenue freeze-out is, but I have my own idea. I hear that phrase and think of a shoot-out, something violent. For a New Jersey man growing up in the 1960s I bet the conservative society he lived in felt violent in its own way. Yet later Springsteen sings about how his sideman Clarence Clemons and him are gonna bust the city in half with a Tenth Avenue freeze-out of their own. I take that to mean they’re turning the cultural pressure against them the other way around with the power of music.

Nobody in the E Street band had power behind them quite like Clarence Clemons. Clemons was the group’s saxophonist, and man could he play. His work on this album is some of the best musicianship on any rock record. He is the secret sauce that takes the album from great to incredible. Whether it’s him playing along with the guitar on “Thunder Road”, his shimmering squawks on “Night”, his perfect call-and-response on “She’s the One”, or the divine solos on “Born to Run” and “Jungleland” Clemons’ sax is always standout.

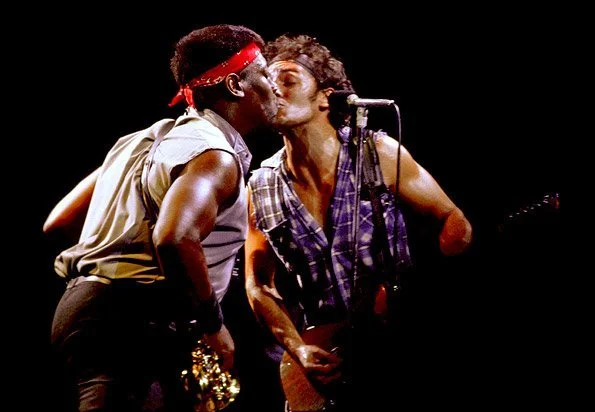

Clemons performed with Springsteen until his death in 2011, and the two were one of rock’s most iconic duos. One thing that set them apart was that they frequently kissed on stage. Neither man claims queerness as a part of their identity, but the two men shared a bond that can only be called love. For all that Springsteen frequently engaging in gay interracial love on stage for thousands to see in the homophobic seventies and eighties should have been controversial, it really wasn’t. The kiss was not an expression of queer love that would only be accepted decades later, but the sheer joy performing brought them. Springsteen was one of the guys, and he could push boundaries like that in the cleanest of ways. To the public, it was brotherly love. Though I’d bet many queer concertgoers saw that and felt like they had more of a place in the world.

Springsteen and Clemons share a kiss in front of a microphone

There’s other queerness on Born to Run as well. It’s in Springsteen writing about being outside of mainstream society and searching for a place where you’ll find acceptance, and it’s also on “Backstreets”. The lengthy A-Side closer sees Springsteen write about a relationship between his narrator and an ambiguously gendered friend, or perhaps lover, named Terry. The song isn’t 100% clear about everything in its narrative beyond the tragedy of relationships falling away in time, but even if the song is 100% heterosexual or platonic I still say it’s queer. The bulk of the song is Springsteen shouting about “hiding on the backstreets”, and what could encapsulate the early 70s queer experience more than finding a beautiful joy you have to hide.

But the shining moment of the album, Springsteen’s career, and perhaps music as a whole is the album’s title track. If you can listen to “Born to Run” without feeling a deep spiritual awe I question if you’re human. It breaks down before its perfect bridge, only to break down AGAIN before a third verse! Genius! Springsteen has some of his best lyrics right at the opening with, “In the day we sweat it out on the streets of a runaway American dream/ At night we right through mansions of glory in suicide machines”. Though every “HUH” “WOAHHHH” Springsteen belts out is amazing, but “Born to Run” is a vocal performance like nothing else. There’s nothing else like the way he transitions from his head voice to his chest voice as he sings “Just wrap your legs ‘round these velvet rims and strap your hands ‘cross my engines!” Or his incredible delivery on, “I want to die with you and me on the street tonight in an everlasting kiss! HUH!” And the Glockenspiel! How the fuck is this song so good it uses a Glockenspiel!!! What rock song uses a Glockenspiel!!!!!! Usually when a rock band adds in orchestral elements it’s to speak on something big and universal like on “You Can’t Always Get What You Want”, but Springsteen just uses it on a song asking a woman to run away with her.

That’s what’s so American about the album. It’s not interested in the big questions, and in tossing the big things away it somehow gets bigger than the biggest questions. It’s arrogant and youthful. It wants to go to the metaphorical West, with all the danger and opportunity involved in that. And though Springsteen makes that journey thrilling and powerful, he doesn’t forget the cost. Going West is not just an adventure, it’s the sun setting, a metaphorical or literal death. We see that narrative in “Meeting Across the River”, where Springsteen’s character seems like he won’t survive his encounter with organized crime, but it’s at its most powerful in “Jungleland”.

Originally, I titled this article “Bruce Springsteen and the Great American Lie”. The point would be that while Springsteen embodies many of the things I love about America, we lost the fight for the nation’s soul. We still have a world of people born to run from death trap towns, except now the only place you can run to is another country (and that’s if you’re lucky). Maybe that’s right. Maybe the punks were right to leave behind the peace, love and hope of the 1960s. Somehow, despite how shitty everything is, that isn’t the article I wrote.

“Jungleland” is an overview of a soldier Springsteen calls The Rat returning home from the Vietnam war and facing an America defined by love, violence, rebellion, cars, and music. Springsteen combines all of those, singing of kids flashing guitars just like switch-blades, and a ballet being fought in the alleys. The core narrative sees The Rat have a brief love affair before “in the tunnels uptown, the Rat’s own dream guns him down”. In his pursuit of fame, or power, or freedom, he dies. Springsteen writes, “No one watches when the ambulance pulls away/ Or as the girl shuts out the bedroom light”. On “Thunder Road”, Springsteen sang that he wasn’t a savior, but he isn’t a nihilist either. Born to Run sounds like everything propaganda makes America out to be, and though the lyrics complicate that fantasy, “Jungleland”s final verse is a commentary on the world as a whole, or perhaps the rock scene. There’s a bit of hopelessness in it, but somehow the words bring me hope. At some point, people gave up, but the fight can live on. So on this Fourth of July I won’t be enjoying the flags and fireworks. But I won’t give up either. The following lyrics give me a resolve I can’t quite place, so I’ll leave The Boss’ words with you in the hope that you find some purpose standing against the fiery streets and stationary poets. Happy Independence Day.

Outside the street’s on fire in a real death waltz

Between what’s flesh and what’s fantasy

And the poets down here don’t write nothing at all

They just stand back and let it all be

And in the quick of the night

They reach for their moment and try to make an honest stand

But they wind up wounded, not even dead

Tonight in Jungleland